Point Guide

Common Projectile Points of the Upper Mississippi River Valley

Hand holding projectile points. by: Robert Boszhardt

Hand holding projectile points. by: Robert Boszhardt

If you would like help identifying an artifact in the Upper Mississippi River Valley or the Upper Midwest please email Jean Dowiasch at Jean. Include in your email a description of the item, where it was found, and attach a picture of the artifact with a scale. Responses will be sent as soon as possible. For help identifying artifacts found outside the Upper Midwest contact that state’s archaeologist. Link to a list of state archaeologists can be found online.

Introduction

Projectile points are tips fastened to the ends of spears, darts, and arrow shafts. In prehistoric North America, they were made from a variety of materials, including antler, bone, and copper but most, at least most that have preserved, were made from stone. The vast majority of these were made by chipping various types of “flint” to shape the projectile point for penetration, cutting, and hafting. Projectile point styles changed through time, much like automobile styles. Sometimes these changes reflect technological shifts, while other times they appear to be simply fads. In either case, it is somewhat astounding how widespread the use of certain projectile point styles was during particular periods of midwestern prehistory. For example, Paleo-Indian fluted spear tips, dating between 11,300 and 10,200 years ago (uncalibrated), have been found in every state between the Rocky Mountains and the Atlantic Ocean. Several thousand years later, side-notched forms were being used by Archaic cultures throughout much of eastern North America. At the transition from Archaic to Woodland traditions there was a widespread shift to contracting stemmed point types, and toward the end of prehistory virtually every culture adopted unnotched triangular arrow tips.

Although many basic point styles were widespread, they often have a variety of regional names. For example, contracting stemmed points are called Waubesa in Wisconsin and the Upper Mississippi Valley, and nearly identical points are called Belknap or Dickson in Illinois and Gary points to the south and east. While there are often modest regional variations in point types, there is rarely evidence of individual expression. Point makers in general were conformists and manufactured tips according to prevailing culturally accepted styles. For this reason archaeologists work diligently to develop regional projectile point chronologies that recognize patterns of changing shape through time. These are based on the premise that once a distinct style is directly dated by carbon 14 association, then similar points can be confidently attributed to the same age. All ages included in this guide are uncalibrated. This cross-dating can be applied to points found in excavations, plowed fields, or in private collections.

A number of projectile point guides cover various styles found in the Upper Mississippi Valley. This page is adapted from a published version through the University of Iowa Press, A Projectile Point Guide for the Upper Mississippi River Valley, and includes only ten of the more common point types found in the Upper Mississippi River Valley. This electronic version also contains links to related sites but does not include references to the original type definitions, which are available in the published version. Two other recommended print guides that overlap this area are Justice’s Stone Age Spear and Arrow Points of the Midcontinental Eastern United States and Morrow’s Iowa Projectile Points. Several price guides are also available, but most are based on undocumented collections, and all contribute to the destruction of the archaeological record by inevitably disconnecting the locational context from artifacts through selling.

Point typology is a tricky business. We know that basic stylistic patterns changed through time, and we have a fairly good regional chronology of shapes, but many points do not readily conform to “type” examples. Some characteristics, such as corner-notching, seem to have been popular during more than one period, so we may need to look for more subtle ways to determine the ages of specific points. Dating points is always a problem with surface finds, yet with avocational and professional archaeologists sharing knowledge, we can detect more precise patterns and associations. Some corner-notched points are found at sites with pottery, others at sites without pottery. Some may be made of heat-treated chert, others of silicified sandstone. Some may have basal grinding, others not. These kinds of “attributes” can help segregate similar looking points that are from different periods. Sooner or later, each variety will be found in datable contexts, and we will then be able to determine their ages directly. Thus, point guides will need to be refined and updated, a process made easier through the Internet. You can help with this continual process by recording your finds and letting archaeologists document them through photography and measurements.

Identifying the source of the stone used to manufacture specific points can also be difficult. Some materials such as Knife River flint and jasper taconite are fairly distinctive, and it is generally not difficult to separate Prairie du Chien chert from Galena or Moline cherts. However, nearly all flint sources exhibit stone of considerable variation in color and quality, and there are many look-alikes. For example, until the 1990s nearly every silicified sandstone artifact found in the Upper Mississippi Valley was classified as having been made of material from the well-known Silver Mound source in western Wisconsin. But subsequent identification of numerous other silicified sandstone source areas, including several extensive prehistoric workshops that have produced flakes of color and texture that rival that of Silver Mound, make definitive identifications problematic. Because specific sources are usually from discrete geological formations, fossil inclusions, structural properties, and mineralogical content are useful keys for identification. For example, a distinctive attribute of Burlington chert is the inclusion of fossil crinoids, but these are sometime microscopic. Mineral and structural analyses often require specialized technologies that are generally done at geological laboratories and usually involve partial destruction of a specimen, such as thin sectioning or neutron activation analysis. Fortunately, new and less-destructive analyses are continually being developed. Because of the importance of material identification to understanding past cultural ranges and interaction networks, many professional archaeological institutes have established comparative lithic collections with examples from source areas.

Stewardship

Many people collect spear tips, arrowheads, and other artifacts from plowed fields in the Upper Mississippi Valley. Besides being a pleasant hobby, collecting these artifacts can tell us which culture lived at each site, how old the site is, how people survived, and which trade networks they may have used. Archaeology has a long history of private collectors making significant contributions by sharing their knowledge. Unfortunately, a few untrained people dig into sites or actively buy and sell artifacts, forever destroying critical information needed to interpret the past.

Archaeological sites are nonrenewable resources of our collective heritage. Once destroyed they are gone forever, and with them goes all potential understanding of the past cultures that occupied those sites. In the 130 years from 1850 to 1980 farming, town development, and road construction obliterated nearly 80 percent of the thousands of mounds that once dotted the Upper Mississippi Valley before legislation finally protected those that remained. Now urban sprawl has accelerated the destruction of the irreplaceable archaeological record. It is imperative that we all contribute to preserving as much as possible. Collecting artifacts gives you two options: you can do it ethically and contribute to an understanding of the past, or you can do it selfishly and destroy the record. Note that ethical collecting begins with landowner permission, and it is illegal to collect from any public land, including nearly all of the Upper Mississippi River floodplain. Once permission is obtained from private landowners, you can contribute to archaeological research by following these few simple practices.

Record your find

When you find artifacts, note where you found them as precisely as possible. In the long run, these will be much more valuable to you than a set of artifacts from places long since forgotten. Keep items found at individual sites separate from those found elsewhere. Simple recording systems such as numbering sites works very well. For example, keep all artifacts found on Site 1 together, or label them as such when mixing with others for display. Keeping a notebook with sketch maps of sites is extremely important. An example of a site recording form follows. You could also mark sites on a county map or even a highway map. The best maps are U.S. Geological Survey topographical quadrangles, which are becoming more easily available in digital form through commercial vendors or via the Internet.

For storing, wrap special artifacts separately to prevent them from getting nicked by knocking against other artifacts. Too often, well-intentioned people have dumped coffee cans or old cigar boxes full of artifacts onto our lab tables revealing not only new information but also new breaks and a small pile of fresh chips. Take care of your artifacts; they are a priceless record of the past and are irreplaceable!

Contact an archaeologist

Each state has a state archaeologist, and many colleges and museums have archaeologists who would be happy to photograph your finds and record the information. Rest assured that archaeologists will not confiscate your artifacts, steal your site, or broadcast its location. You will be helping to piece together essential knowledge of the past. In return, you will learn how old your artifacts are, what they are made of, and what they were used for.

Do not buy, sell, or trade artifacts

Buying and selling artifacts not only encourages looting, but once sold, the most important information—site location—is gone forever. It also encourages the manufacture of fraudulent artifacts, and all buyers eventually get taken because fakes can be impossible to distinguish from authentic artifacts. Flintknappers have been producing replicas and fakes for well over a century, and a 1994 survey of modern flintknappers revealed that as many as 1.5 million replica-fakes are being made every year. If you don’t know who found it and where it was from, there’s a good chance you are buying a fake.

If you have a collection and you can no longer keep it, either donate it to a state historical society or university with a curation facility, or pass the collection on to the next generation or to someone else who you know will cherish and maintain the collection. This ensures that collection information will follow the actual artifacts. The key is to make sure that information about the material and where it was collected remains with the collection. Donations to nonprofit organizations are usually tax-deductible.

Never dig or excavate a site without proper supervision

Archaeological sites cannot be replaced. Once a site is dug improperly, it is destroyed and cannot be reconstructed. There are ample opportunities to participate in professional excavations throughout the Midwest.

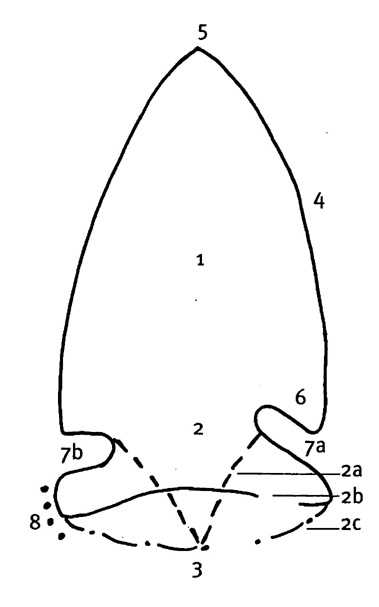

Projectile Point Features and Terminology

Drawing of a projectile point. Blade: The cutting portion of the point above the hafted stem.

Drawing of a projectile point. Blade: The cutting portion of the point above the hafted stem.- Stem: The modified bottom of the blade for hafting onto a shaft or handle.

- Contracting: A haft stem that tapers from the shoulder to the base.

- Concave: An edge (usually at the base) that curves inward.

- Convex: Outward curving edges.

- Base: The very bottom of the point.

- Edge: The sides of the blade (may be serrated, beveled [steep angle], pressure flaked, etc).

- Tip: The pointed top of the blade.

- Shoulder: The wide portion of the blade immediately above the stem.

- Notching

- Corner-notched: Notches oriented at an upward angle from the basal corners.

- Side-notched: Notches oriented perpendicular to the length of the point.

Points

Alphabetical

Points

Cultural Traditions

Early Paleo Indian Fluted Spear Forms

Late Paleo Indian Lanceolates

Early Archaic Stemmed and Corner Notched

Middle Archaic Stemmed and Side Notched

Late Archaic Stemmed and Corner Notched

Early Woodland Stemmed

Middle Woodland Broad Corner Notched

Late Prehistoric Woodland/Oneota Arrowheads

The web-based Projectile Point Guide was created with a grant from the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse Foundation.