Posted 1:43 p.m. Wednesday, July 22, 2015

They dive into the pitch-black waters of the Caribbean Sea 45 minutes after sunset, searching for one of the most dazzling displays in the natural world.

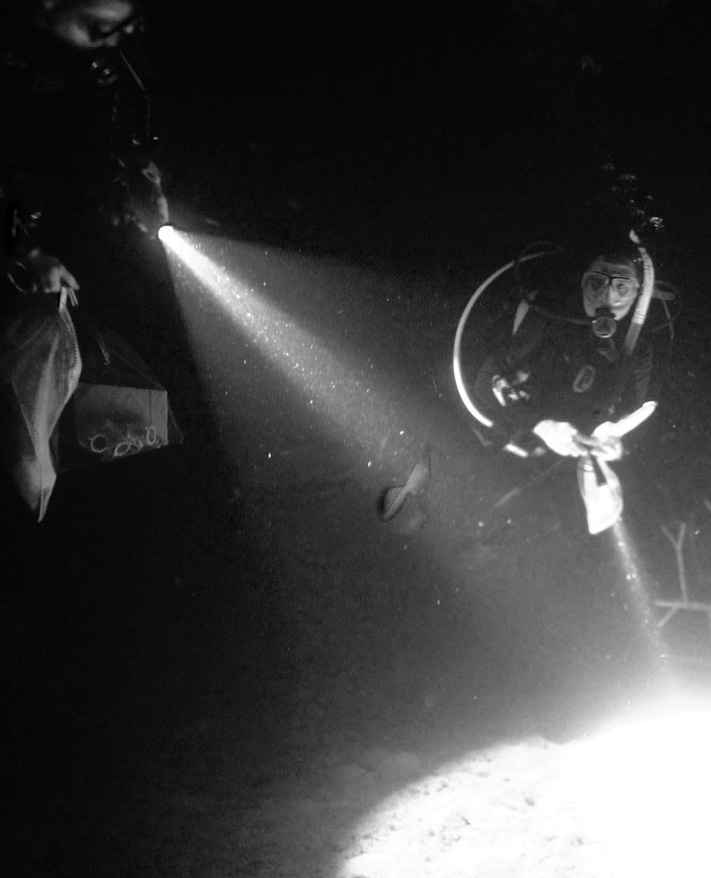

When a fish consumes an ostracod, the ostracod emits large amounts of luminescence in what is thought to be an anti-predator response. The light in this image is produced by an ostracod as it is being chewed by a fish.[/caption]

When a fish consumes an ostracod, the ostracod emits large amounts of luminescence in what is thought to be an anti-predator response. The light in this image is produced by an ostracod as it is being chewed by a fish.[/caption]

National Science Foundation grant funds UWL research on tiny creatures in the Caribbean

They dive into the pitch-black waters of the Caribbean Sea 45 minutes after sunset, searching for one of the most dazzling displays in the natural world. “The sun and moon have to be absent because they don’t like light,” explains UW-La Crosse Biology Professor Gretchen Gerrish. Gerrish, her UWL student research assistants, and a team of researchers from four other universities are searching for what Gerrish calls “a symphony of lights” or more commonly, “fireflies of the ocean.” Gerrish recently earned a $346,000 National Science Foundation grant to study these tiny, shrimp-like crustaceans called marine ostracods, part of a more than $1 million collaborative grant with the four other universities. Ostracods emit tiny packets of chemicals that produce bright blue lights in the deep sea. The lights flash in specific patterns and directions to attract mates, creating a beautiful display and a puzzle for scientists. [caption id="attachment_42282" align="alignright" width="350"] UW-La Crosse Biology Professor Gretchen Gerrish. Looking at the camera lit by UWL student John Frawley during a night dive collecting ostracods Monday, June 8 in the Caribbean Sea.[/caption]

More than 64 flashing patterns have been observed throughout the Caribbean Sea, but only one third of the ostracod species have been collected and described scientifically. Gerrish’s research will add to the body of knowledge surrounding ostracod species identification and evolution while training students in scientific research.

Two of her students traveled with her to Jamaica June 3-18 to collect ostracod samples and also record their light displays on video. That video will be used to collect data on variation in the bioluminescent displays. And the video will be shared with filmmakers from Ammonite, a United Kingdom company, who are working on a documentary narrated by David Attenborough about bioluminescence, likely to be aired on a major cable network.

“This is a huge outreach opportunity to educate people about these unique systems and create enthusiasm for the natural world,” says Gerrish.

[caption id="attachment_42289" align="alignright" width="200"]

UW-La Crosse Biology Professor Gretchen Gerrish. Looking at the camera lit by UWL student John Frawley during a night dive collecting ostracods Monday, June 8 in the Caribbean Sea.[/caption]

More than 64 flashing patterns have been observed throughout the Caribbean Sea, but only one third of the ostracod species have been collected and described scientifically. Gerrish’s research will add to the body of knowledge surrounding ostracod species identification and evolution while training students in scientific research.

Two of her students traveled with her to Jamaica June 3-18 to collect ostracod samples and also record their light displays on video. That video will be used to collect data on variation in the bioluminescent displays. And the video will be shared with filmmakers from Ammonite, a United Kingdom company, who are working on a documentary narrated by David Attenborough about bioluminescence, likely to be aired on a major cable network.

“This is a huge outreach opportunity to educate people about these unique systems and create enthusiasm for the natural world,” says Gerrish.

[caption id="attachment_42289" align="alignright" width="200"] Gretchen Gerrish's research is in collaboration with University of California-Santa Barbara, California State University Los Angeles, Cornell University and University of Kansas.[/caption]

Gerrish’s work specifically aims to better understand the evolution of the light displays marine ostracods emit during courtship and evolution of their ability to create light or bioluminescence. While ostracods use their bioluminescence to defend themselves from prey in waters all over the world, The Caribbean Sea is the only place where luminescent mate attraction in ostracods has been observed.

Gretchen Gerrish's research is in collaboration with University of California-Santa Barbara, California State University Los Angeles, Cornell University and University of Kansas.[/caption]

Gerrish’s work specifically aims to better understand the evolution of the light displays marine ostracods emit during courtship and evolution of their ability to create light or bioluminescence. While ostracods use their bioluminescence to defend themselves from prey in waters all over the world, The Caribbean Sea is the only place where luminescent mate attraction in ostracods has been observed.

“The reason the scientific community is excited about this system is that there is high diversity within the Caribbean group and they appear to have very fast rates of divergence (organisms from a common ancestor evolving into different forms)” says Gerrish. “Our hypothesis is that they are evolving very fast because of their reproductive behavior.”

Studies at sea: Getting students on board

[caption id="attachment_42287" align="alignleft" width="593"] Mitch McCloskey, a UWL sophomore this fall, pictured in his scuba gear, preparing for a night of research in the Caribbean Sea.[/caption]

UWL student Mitch McCloskey first heard about marine ostracods during a football recruiting trip to UWL. He wanted to see a biology lab and ended up meeting Gerrish who shared her ostracod research.

McCloskey’s dream since age 5 was to become a marine biologist. To have the opportunity to do that relatively close to home in Madison was a big factor in his decision to attend UWL.

Today he is no longer playing UWL football, but his marine biology ambitions are growing. After a semester of research in her lab, Gerrish invited McCloskey to join the NSF grant research team in the Caribbean. He calls it an “honor” and thanks Gerrish for the opportunity. “To be invited to be part of research like this as a freshman and undergrad is pretty much unheard of,” he says.

McCloskey’s role was managing the high-tech camera that recorded the marine ostracod light displays under water. The aquatic science major had spent long hours reading about what’s already been discovered in science journals, but the best part of science, he adds, is seeing how people figure it out. He learned a lot about problem solving.

“In science you are doing things no one has done before — except running the camera — that has an instruction manual,” he quips.

He calls the research the most important part of his college experience. “I’m learning how to do what I want to do for the rest of my life,” he says.

More than half the NSF grant funding is to train students in techniques associated with specimen collection and preservation, DNA and behavioral analysis, writing and outreach over the next three years, says Gerrish. She has watched her students — majors in aquatic science and pre-med — grow more confident in their science skills during the trip and subsequent lab research.

[caption id="attachment_42285" align="alignleft" width="305"]

Mitch McCloskey, a UWL sophomore this fall, pictured in his scuba gear, preparing for a night of research in the Caribbean Sea.[/caption]

UWL student Mitch McCloskey first heard about marine ostracods during a football recruiting trip to UWL. He wanted to see a biology lab and ended up meeting Gerrish who shared her ostracod research.

McCloskey’s dream since age 5 was to become a marine biologist. To have the opportunity to do that relatively close to home in Madison was a big factor in his decision to attend UWL.

Today he is no longer playing UWL football, but his marine biology ambitions are growing. After a semester of research in her lab, Gerrish invited McCloskey to join the NSF grant research team in the Caribbean. He calls it an “honor” and thanks Gerrish for the opportunity. “To be invited to be part of research like this as a freshman and undergrad is pretty much unheard of,” he says.

McCloskey’s role was managing the high-tech camera that recorded the marine ostracod light displays under water. The aquatic science major had spent long hours reading about what’s already been discovered in science journals, but the best part of science, he adds, is seeing how people figure it out. He learned a lot about problem solving.

“In science you are doing things no one has done before — except running the camera — that has an instruction manual,” he quips.

He calls the research the most important part of his college experience. “I’m learning how to do what I want to do for the rest of my life,” he says.

More than half the NSF grant funding is to train students in techniques associated with specimen collection and preservation, DNA and behavioral analysis, writing and outreach over the next three years, says Gerrish. She has watched her students — majors in aquatic science and pre-med — grow more confident in their science skills during the trip and subsequent lab research.

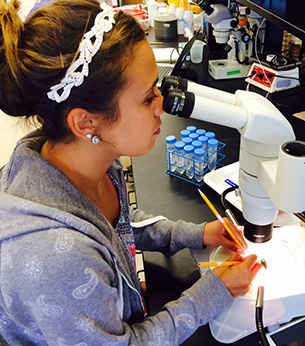

[caption id="attachment_42285" align="alignleft" width="305"] Biology Major Alexa Aguirre dissecting a marine ostracod. She uses pencil erasers with tiny wires poked inside them.[/caption]

At first the thought of dissecting a sesame-seed sized organism under a microscope sounded undoable to Biology Major Alexa Aguirre.

“I was like holy cow — I have to dissect that microscopic thing?,” she says.

A week into the dissections, she did it with ease. Her work is helping to identify three new species of ostracods they found in the Caribbean.

“Anything hands-on is such a different experience from lectures,” she says. “I’ve learned so much. I’m hands-on. That’s how I learn.”

John Frawley, a UWL senior in the fall, plans to attend medical school after UWL. He received an Undergraduate Research and Creativity grant to support his research.

“Genetic techniques similar to what I’m using in lab are used in medicine to find genetic disorders,” he says. “And it’s important for me to experience field research and the frustrations that can go along with it.”

Moreover, he and the other students are able to work with researchers who want to help them improve as scientists and researchers, and share their enthusiasm, he says.

“It’s fun to work with people so excited about what they’re doing,” says Frawley.

Biology Major Alexa Aguirre dissecting a marine ostracod. She uses pencil erasers with tiny wires poked inside them.[/caption]

At first the thought of dissecting a sesame-seed sized organism under a microscope sounded undoable to Biology Major Alexa Aguirre.

“I was like holy cow — I have to dissect that microscopic thing?,” she says.

A week into the dissections, she did it with ease. Her work is helping to identify three new species of ostracods they found in the Caribbean.

“Anything hands-on is such a different experience from lectures,” she says. “I’ve learned so much. I’m hands-on. That’s how I learn.”

John Frawley, a UWL senior in the fall, plans to attend medical school after UWL. He received an Undergraduate Research and Creativity grant to support his research.

“Genetic techniques similar to what I’m using in lab are used in medicine to find genetic disorders,” he says. “And it’s important for me to experience field research and the frustrations that can go along with it.”

Moreover, he and the other students are able to work with researchers who want to help them improve as scientists and researchers, and share their enthusiasm, he says.

“It’s fun to work with people so excited about what they’re doing,” says Frawley.